The 1974 Ulster Workers' Council strike and why I still care about Northern Ireland

Reflections on a forgotten coup d'État in 1970s Europe

My father was born in (London)derry in 1941 as part of a community of upper-middle class Protestants whose roots in Ireland dated only as far back as the early 19th century. As I recently found out, my father’s family is basically 100% Scottish and its roots in Scotland go back at least to the 15th century. Nevertheless, when I was growing up, I understood my father’s family to have come from Ireland, and that my dad identified as Irish. Indeed, on the basis of the 1998 Good Friday agreements, I have recently been able to claim Irish citizenship on account of my father’s birth in a city that is (still) actually part of the United Kingdom.

That said, I can’t say I’ve ever had much affinity for Ireland or its culture. When I was a child and living in England during the 1980s, I was dragged across the Irish Sea every year or two to visit a series of elderly relatives to whom I felt little connection. For me, Northern Ireland was dour, grey, backwards. In contrast the South of England was modern, progressive, even sunny (comparatively!).

The last time I travelled there was in 1993, when I was 16 years old: in other words, before the end of the “Troubles” (although my family and I never really used that term). I never felt any type of danger traveling there, just bored and out of my element (as a child, I was much, much more worried about the possibility of a USSR/USA nuclear war than anything going on in Northern Ireland). In reality, even after I moved to the United States in 1985, my understanding of the political/military situation in Northern Ireland was like much of the English population. I was largely indifferent to the low level violence it generated, just another grim part of the background of British life in the 1980s. Like much of the English (and, to a lesser extent, Scottish) population, I didn’t feel strongly whether or not Ulster remained a part of the United Kingdom or not—about which Northern Ireland’s Protestant community was (and continues to be) all too aware.

When I was a teenager living now living in the United States in the 1990s, my feelings changed. With my family, I had moved to a small suburban community just outside Philadelphia where it wasn’t uncommon to see Irish flags flying from porches and pro-IRA bumper stickers on cars. Indeed, an Irish social club/bar was located literally a block from my house that had become famous for supporting the IRA (see: https://www.irishstar.com/news/pennsylvania-news/macswiney-club-100-year-old-29938299). I came to realize that, in the United States, Irish culture is highly romanticized and to the extent that anyone cared about the island’s politics, support for the Irish Republican cause was hegemonic. While my dad was always deeply fond of Ireland writ large, I know the cartoonish romanticization of the Republican cause bothered him. In an act of teenage iconoclasm and a search for rootedness as an English immigrant in the United States, I proudly claimed my support for Protestant Ulster. Didn’t the American Irish realize that the majority of the population in Ulster wanted to be part of the United Kingdom? Didn’t they realize that their position was thus inherently anti-democratic? (This was very likely true at the time, although I am much less sure it is so now, given demographic change and Brexit)

At that time, I didn’t realize that the Irish Republican cause was largely coded as a left movement and support for Ulster was coded as right wing. It was not until my late 20s that I became aware of this political coding. Even though I identified as broadly left of center politically in my 20s, I really didn’t change my views as a result. I came to recognize some of the politically and culturally unattractive aspects of Ulster Protestant culture, but I was also drawn to parts of this culture as well. I don’t have any desire to adopt the views of Democratic Unionist Supporters) DUP supporters, but I must confess things like loyalist paramilitary anthems or Glasgow Rangers’ loyalist fan culture are, to an certain extent, stirring (even if the sentiments expressed are things I don’t want to associate myself with).

I suppose, again, for me, it is a culture from which I have come in part, and that is worth something to me. I have always at some level struggled internally to find my place in American society and I my feelings towards the country are somewhat ambivalent. England, of course, could offer an identitarian substitute. But somehow, the Ulster Protestant identity is more that of an underdog, at least in the context of American culture. I believe this is what draws me towards it at times, even as I have become fully aware of its less attractive political coding.

In sum, writing about Northern Ireland is thus also partly a personal history. I first became aware of the 1974 Ulster Workers Council’s (UWC) strike for the first time in my 30s. Looking back, I felt amazed someone like myself who has a fairly significant connection to and at least some historical knowledge of the conflict’s history had never have heard of it. I knew very well events like 1972’s Bloody Sunday, the 1981 IRA hunger strike, or the IRA bombing of the 1984 Conservative Party conference. While one can certainly make an argument that all of these events are more important in the context of the Troubles themselves, none of them surprised me or made me care particularly about the conflict as something of great importance.

I think this is because the way the UWC strike unfolded and the fact it successfully toppled the fragile power-sharing agreement put in place by the British government violated my mental model of where “things like this” happen. That is, the UWC strike could perhaps be described as a successful coup carried out by minority of militant Protestant Loyalists. In my mind, “things like this” didn’t and don’t happen in western Europe in the late 20th century. In this sense, it is for me different than something like Bloody Sunday (again, arguably a more important incident in the context of the Troubles), which I can categorize alongside political violence in other comparable parts of the world during this era (e.g. the Kent State massacre in the United States, the 1968 youth revolts, Baader–Meinhof/Brigate Rosse terrorism, etc.).

What does this sense of intellectual excitement the discovery of this episode mean in a broader sense? Uncharitably, it shows that I still carry an unconscious about what parts of the world are “civilized” and “advanced” and which parts aren’t and what one should expect happens in the one and in the other. But it also shows I think that we in the “developed” world overrate the stability and permanence of our present political and social reality. With the arrival of Trump and a legion of other “populists” on the global political scene, maybe these comfortable assumptions have been shaken a bit. Still, I think we as citizens of countries in the “developed” world still largely assume subconsciously that democracy and the rule of the law are the natural order of things. I count myself among this we still, but I intellectually know the idea that “things will work out fine in the end” is probably unjustified. Democracy, liberalism, and the rule of law remain a fragile experiment even in the parts of the world where they have their deepest roots.

The immediate backdrop for the 1974 UWC strike was the British government’s attempt that year to put in a place a system of home rule in Northern Ireland, whereby the Protestant and Catholic populations would share power on a relatively equal. This new governmental system was the British government’s first serious attempt to replace the previous governing system, which had collapsed under the weight of what had effectively become a civil war between the country’s Protestant and Catholic communities (“the Troubles”). Of course, the previous governing system instituted when Northern Ireland was founded as a state in 1921 was highly problematic and led to its ultimate collapse. Simply put, Northern Ireland’s original governmental structure had been designed to permanently lock the country’s Catholic minority out of exercising any kind of power. Indeed, in the roughly 50 years of the previous system’s existence, sectarian Protestant politicians held all important ministerial positions and made all important decisions. By the 1960s, the Catholic minority had largely given up in participating in what they saw as fundamentally un-democratic system. Instead, young Catholic activists turned their attention to non-parliamentary political action, instigating a civil rights movement modeled on the African American freedom movement then reaching the peak of its powers in the United States.

The response of the Protestant community to this new form of Catholic political activism was largely one of radicalization. With some exceptions, Protestant politicians and a significant part of the broader community of which they were a part largely refused to consider any real change. From a certain perspective, this response is not easy to understand. The mainstream of the civil rights movement weren’t asking for Irish reunification or even for Protestant leaders to relinquish power. They were only asking for a say in the governing of the province, particularly with regards to the distribution of public resources like housing and education. While it is true the largely dormant Irish Republican Army (IRA) had re-awakened and was growing into significant force, the IRA remained in the early 1970s a minority phenomenon. If anything Protestant intransigence had provided the largest spur to the IRA’s growth, not the demands of the civil rights movement.

Yet, much of the Protestant community didn’t necessarily take the civil rights movement’s relatively modest demands literally. Rather its very existence was fed into a broader moral schema the Protestant community had developed of itself as an embattled pioneer community, a beachhead of a civilized British empire in a land of backwardness, poverty, and superstition. The community’s sense of being under siege was further exacerbated by the feeling that the British people and its government didn’t really care much about them and were happy enough to make a deal with the Irish government to re-unify the island. Unsurprisingly, the rejuvenation of the IRA and its violence worked to further harden these narratives, spurring the growth of a series of Protestant paramilitary groups, most notably the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and the Ulster Defense Association (UDA).

These paramilitary forces were central to the UWC strike effort, for which planning began in earnest in late 1973, in advance of the inauguration of the new power sharing agreement (which was to begin on January 1, 1974). When the strike began on May 14, 1974, almost all observers dismissed its significance. Indeed, loyalist strikes had become a common occurrence which typically only lasted a few days at most and had not been able to cause widespread disruption. However, the extent of planning as well as the deepening connection between Protestant trade unions and paramilitary groups meant the May-June 1974 episode would be of a different magnitude.

Glenn Barr, leader of the strike coordinating committee, is probably the best example of the this deepened connection between politics, trade unionism, and paramilitary activity. Barr’s principal occupation was serving as an operative for Vanguard, a hardline loyalist political political party with recent origins. The new party began its life as a breakaway from Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) spearheaded by a group of hardliners dissatisfied by what they felt was the overly-accommodation direction of what remained the Protestant community’s hegemonic force. Crucially, Vanguard had close links with the major paramilitary groups including the UVF and UDA. Many of its members also belonged to paramilitary organizations, as was case with Barr who was a member of the UDA. But Barr’s was not just a political activist or a paramilitary member. He had also previously been a unionized worker at the Coolkeeragh power station and thus had important contacts within throughout Northern Ireland’s electricity generation industry. Striker/militant control of this sector would prove crucial.

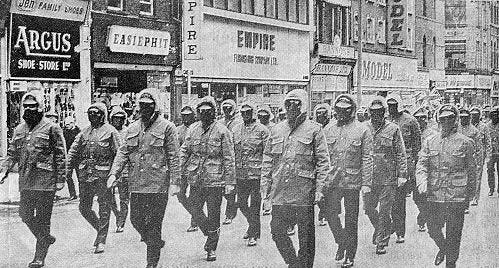

The strike did not begin with great fanfare. On its first morning (Wednesday May 15), 90% of Northern Irish workers still reported to work. However, militant control of the province’s power generation capacity would rapidly change its trajectory. By the afternoon of the 15th, power generation capacity in Northern Ireland had been reduced to 40% of its normal level. At the same time, just as power cuts were beginning to genuinely reduce productivity, UWC militants and loyalist militiamen went around to major employment sites throughout the province and successfully threatened workers to go home. For example, the 8,000 workers at Belfast’s iconic Harland and Wolf shipyard were told any car found in the company parking lot would be set on fire after 2pm. Likewise, masked gunmen arrived at Mackie’s, Belfast’s largest engineering plant, and forced its employees to leave. Outside of larger workplaces, UDA and UVF members went up and down the high streets of towns throughout the province, forcing shop owners to close down.1

By the next morning (May 16), a combination of strikers and militiamen set up roadblocks throughout the province to prevent people from going to work. Masked men with guns and bats manned the roadblocks, adding an additional deterrent. In some cases, violence was deployed against workers who refused to comply. Those who did not had their cars or trucks hijacked and/or set on fire. That evening, the UWC ordered all bars, clubs, and hotels in Belfast to shut down. By morning of May 17, virtually all economic activity in the province had been shut down. The scene that reigned by the weekend were striking. As Robert Fisk, the strike’s most important chronicler, described: “Gangs of Protestants…roamed the main roads into the city (Belfast), stealing cars, lorries, buses and even a crane before setting them on fire.”2

Remarkably neither the police nor the British military was willing or able to do much to stop what basically amounted to a coup d’état. The case of the police is perhaps less surprising. Policing in Northern Ireland was then handled by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), an almost entirely Protestant organization with extensive ties to Loyalist paramilitaries. RUC members were thus in many cases supportive of the strike. The British military’s inaction is a little harder to explain, as its force were drawn largely from elsewhere in the United Kingdom and didn’t contain the same kind of sectarian biases. Theoretically, it also had the most significant coercive resources of any body in the province, as it had been set precisely to prevent the kind of think the UWC was doing from happening. As such, the military came under a lot of criticism for its failure to act decisively, both at the time and subsequently.

The British military did make attempts after the striker’s blitzkrieg to take down road blockades and restore order, although not in a very forceful manner. Still, even if their attempt to restore order had been more aggressive, a far bigger problem remained in that the strikers continued to control power generation and thus economic activity. The British military did not have the necessary expertise or manpower to restart the province’s power generation, meaning the strike would have been able to maintain a good degree of its strength. Further, even if the military did have the ability to take on essential economic activities, that would have put them in conflict with heavily armed and highly motivated Protestant militiamen, thus opening a second insurgency in the province. Ironically, as vehemently as the Protestant population claimed its Britishness, the British army itself was little more than a UN-style peacekeeping force in Ulster.

By May 23, Brian Faulkner, a moderate unionist and beleaguered head of the newly-inaugurated power-sharing executive, described the situation in a meeting with Prime Minister Harold Wilson as such: “It has become increasingly evident that the administration of the country (is) in fact in the hands of the Ulster Workers’ Council. The issue was now not whether the Sunningdale (power-sharing) agreement would or would not survive. The outcome which Protestant extremists sought was without question an independent, neo-fascist Northern Ireland.”3 Taken literally, Faulkner’s diagnosis is inaccurate in that the strikers and their supporters didn’t want a “neo-fascist” government, and they very much didn’t want an independent Northern Ireland. Still, I think Faulkner’s words do capture a certain deeper truth about the moment. The UWC strikers were indeed willing to use radical, anti-democratic methods so that the Protestant community could continue to dominate Northern Ireland’s governance. In this, they made evident the the community’s relatively weak attachment to democracy as well as its openness to a violent, authoritarian politics.

The context in which Faulkner uttered these words occurred in the run-up to a nationally-broadcast speech Harold Wilson would give the next day, which proved to be a significant misjudgment on Wilson’s part. The Prime Minister inflamed Ulster Protestant sentiment, accusing the community of ingratitude and insubordination. As a result, Loyalist sentiment would harden even further in favor of the strike and agains the power sharing agreement. At the start of the new work week on Monday, May 27, the UWC called for a complete stoppage of all essential work, declaring the British army would have to handle all power generation and road haulage. Over the weekend, the British army had in fact taken control of part of the fueling infrastructure, but this partial success was very much an instance of too little, too late. Surrounded in the executive offices at Stormont Castle by Protestant militiamen and striking farmers riding tractors, Faulkner resigned his role as Chief Executive on May 28. He was immediately followed by the other Unionists still participating in the power sharing government, leading to its collapse. The UWC strike had succeeded. There would not be another attempt at political power-sharing between the Protestant and Catholic communities for another generation.4

If I wanted to flatter the sense of the Republican community’s moral righteousness, I might allow myself to comparison the Ulster Protestant community to that of white South African or Rhodesians, French Algeria, or perhaps Israeli settlers on the West Bank and Gaza (or even more controversially, of the Israeli state itself). And indeed these comparisons aren’t entirely superficial. Perhaps the closest analogy would be to that of the French Algerians, another community who viewed themselves as a beachhead for a metropole that didn’t love them back. But there are a few important differences. Unlike the European settlers in Algeria, the Protestant community represented a comfortable majority of Northern Ireland in the late 20th century and much of this population had lived there for several centuries (In a strange way, these facts worked to undercut both community’s moral eschatology of the conflict, as the Protestant community was neither particularly embattled nor particularly “colonial”. ) Further, while there are certain important differences separating the Ulster Protestant and Catholic communities, they aren’t necessarily greater than those separating the English from the Scottish, or the Scottish from the those living in the Republican of Ireland. In the end, all the traditional “nations” living in the British Isles share a certain cultural sensibility, particularly the non-English. They certainly have more in common with each other than they do with, say, Americans. In other words, a basis for cross-cultural understanding had always been higher in Ulster than in some of the other colonial scenarios to which it had been compared.

Perhaps it is this shared cultural understanding that has enabled a shaky, imperfect, and yet real peace to prevail in 21st century Northern Ireland. But, in part, I think the (subconsciously prevalent) idea that Northern Irish Protestants and Catholics aren’t very different after all that has also made the world completely lose interest in the conflict. It is also why an episode like the UWC strike is almost completely unknown and the only book written about the episode has long been out of print.5 After all, many seem to be assuming, should we be surprised if two groups of white Christians with many cultural similarities were able to stop killing each other and share political power? Putting aside the very real possibility that the conflict will re-emerge as the consequences of Brexit play themselves in the years to come, I think this view of the Northern Irish conflict is quite mistaken. I believe this especially in light of events like the largely-forgotten UWC strike of 1974. For me, the strike demonstrate just how fragile the rule of law and democratic institutions are in all societies, even those with a strong liberal, democratic tradition and where group conflict is relatively manageable. In other words, if a coup d’état can happen in somewhere like Northern Ireland in the 1970s, it can happen in many, many other places as well. Today’s Northern Ireland is not the same place it was in 1974, but it is not that different either. As such, it does not take a massive leap of imagination to envision a similar type of political collapse occurring in multiple nations in the developed world under the right circumstances. The Trump-inspired insurrection in the aftermath of the 2020 election should serve as a warning: it really can happen here.

Dominic Sandbrook, Seasons in the Sun: The Battle for Britain, 1974-1949 (Allen Lane: London, UK, 2012), 112-113.

Ibid, 113-116.

Faulkner quoted in Sandbrook 117.

Works informing the narrative of the strike described in this section drawn from: Sandbrook, Seasons in the Sun; Feargal Cochrane, Northern Ireland: The Fragile Peace (Yale University Press: New Haven and New York, 2021); David McKittrick and David McVea, Making Sense of the Troubles: A History of the Northern Ireland Conflict (Viking: London, UK, 2012); and the Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ulster_Workers'_Council_strike)

This book is: Robert Fisk, The Point of No Return: The Strike Which Broke British Ulster (Times Books: London, UK, 1975). Unfortunately, I was not able to track down a copy of this book. I draw some references from via Sandbrook, Seasons in the Sun.